Despite all the advancements in modern science, we still know relatively few reliable facts about the structure of the Earth. We are already reaching out to other planets, yet we have not fully explored the subglacial continent of Antarctica, the ocean depths, or the Earth’s interior. However, humanity is gradually acquiring new knowledge, even if only in small increments, and today we know much more than we did half a century ago.

Facts About the Structure of the Earth:

- Scientists estimate that about 32.1% of the Earth’s mass is composed of iron, which is found in its mantle and core.

- The Earth’s structure still holds many mysteries. It has been proven that the Earth’s core consists of iron, but other minerals are also present, with iron accounting for about 88.8% of the core’s mass.

- Due to the Earth’s slight flattening caused by its rotation on its axis, it is not perfectly spherical. As a result, its diameter at the equator is 43 kilometers (27 miles) greater than at the poles.

- Speaking of the Earth’s structure, it’s important to mention the significance of oxygen. It makes up about 47% of the Earth’s crust, mostly in combination with other elements.

- Although carbon is the foundation of all life on Earth, it accounts for only about 0.1% of the planet’s mass.

- More than 70% of the Earth’s surface is covered by water.

- The Earth rotates rapidly on its axis, but we don’t feel it. If you stand directly on the equator, you would be moving through space at a speed of over 1,600 kilometers per hour (1,000 miles per hour). At the poles, however, you would actually be standing still relative to the Earth’s center.

- The Earth’s atmosphere extends into space for about 10,000 kilometers (6,200 miles), though space is officially considered to begin at an altitude of 100 kilometers (62 miles), and at an altitude of 5 kilometers (3 miles), atmospheric pressure is only slightly more than half of the normal level.

- Despite the limited knowledge of the Earth’s structure, it is well established that the thickness of the Earth’s crust ranges from 6 to about 70 kilometers (4 to 43 miles). It is thinner under the oceans and thicker on the continents.

- The highest point on Earth is the summit of Mount Everest, at 8,848 meters (29,029 feet), while the deepest point is the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, at 10,994 meters (36,070 feet).

- The Earth’s molten core plays a crucial role in its structure, creating the magnetic field that protects our atmosphere from being blown away into space by the solar wind and shields us from solar radiation through the magnetosphere.

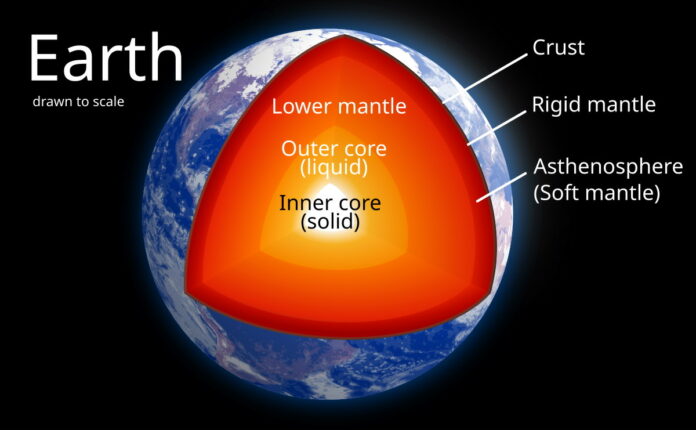

- Scientists believe that the outer part of the Earth’s core is liquid, while the inner core is solid.

- Earth’s Layers: The Earth is composed of three main layers: the crust, the mantle, and the core. The crust is the outermost layer, followed by the mantle, which is much thicker, and the core, which consists of a solid inner core and a liquid outer core.

- Seismic Waves: Much of what we know about the Earth’s internal structure comes from studying seismic waves generated by earthquakes. These waves travel through the Earth and change speed and direction depending on the materials they encounter, providing clues about the composition and state of the Earth’s interior.

- Tectonic Plates: The Earth’s crust is divided into large pieces known as tectonic plates. These plates float on the semi-fluid upper mantle (asthenosphere) and are constantly moving, albeit very slowly. The movement of these plates is responsible for earthquakes, volcanic activity, and the formation of mountain ranges.

- The Moho Discontinuity: The boundary between the Earth’s crust and mantle is known as the Mohorovičić discontinuity, or “Moho” for short. It was discovered in 1909 by Croatian seismologist Andrija Mohorovičić and marks a significant change in the composition and properties of Earth’s materials.

- Temperature Extremes: The temperature inside the Earth increases with depth. The mantle, which extends up to about 2,900 kilometers (1,800 miles) below the surface, has temperatures ranging from 500°C (932°F) to 4,000°C (7,232°F). The core is even hotter, with temperatures reaching up to 5,700°C (10,292°F), similar to the surface of the Sun.

- Magnetic Field Reversals: The Earth’s magnetic field, generated by the movement of molten iron in the outer core, has reversed its polarity many times throughout history. These reversals, known as geomagnetic reversals, happen irregularly, with the last one occurring about 780,000 years ago.

- Gravitational Anomalies: The Earth’s gravity is not uniform everywhere. Variations in the distribution of mass within the Earth, such as mountain ranges, ocean trenches, and dense rock formations, cause small differences in gravitational pull at different locations.

- The Earth’s Core Growth: The Earth’s inner core is slowly growing as the outer core solidifies and transfers heat. This growth happens at a rate of about 1 millimeter per year, but it’s balanced by the gradual cooling of the planet over billions of years.

- Deepest Artificial Hole: The deepest hole ever drilled by humans is the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia, which reaches a depth of 12.3 kilometers (7.6 miles). Despite this impressive depth, it only penetrates a small fraction of the Earth’s crust, highlighting how little we’ve physically explored the Earth’s interior.

- Mantle Plumes: Some volcanic islands, such as Hawaii, are formed by mantle plumes—upwellings of abnormally hot rock from deep within the mantle. These plumes can create volcanic hotspots that remain stationary while tectonic plates move over them, forming chains of volcanic islands.

- Isostasy: The Earth’s crust “floats” on the more fluid mantle beneath it in a state known as isostasy. When large ice sheets melt or mountains erode, the crust can slowly rise or sink to maintain gravitational balance, a process known as isostatic rebound.

- Core’s Role in Earth’s Rotation: The Earth’s inner core may rotate at a slightly different speed than the rest of the planet. This differential rotation is thought to affect the length of the day over long periods, contributing to the gradual changes in Earth’s rotation speed.